This post was prompted by a webinar I gave on behalf of Citrix/GoToWebinar on 6th July 2011 and originally posted as a guest post on the Learning Pool blog. I’ve made a few changes to it here.

Looking Back

eLearning has been with us in one form or another for at least the past 50 years, maybe longer.

eLearning has been with us in one form or another for at least the past 50 years, maybe longer.

Probably the first player on the enterprise eLearning block was the University of Illinois’ PLATO learning management system, built in 1960 to deliver training through user terminals (which, even then, had touch-screens).

Some would argue that quite a few of today’s LMS offerings haven’t advanced a great deal from PLATO. They serve up content and track activity.

Plato IV LMS circa 1972

Personal Journey

My own exposure to eLearning began back in 1964 when learning speed reading via an electronic system at my secondary school. The speed reading machine was about the size of a large refrigerator and probably weighed roughly the same (maybe they even shared components). However despite the obvious limitations, technology was making its way into learning through a number of routes even back then.

My first involvement in working with learning technologies that we’d recognise today was when tutoring at the University of Sydney in the early 1970s. In the School of Biological Sciences lectures were pre-recorded and delivered across the campus on TV screens and the labs were supported with tape-driven experiential learning activities. Content was still analogue, but delivered in ‘e’ format.

My exposure to eLearning in the early 1980s really got me ‘hooked’ on the potential of technology in learning. At the time I was running online collaborative learning courses. The ‘hooking’ was reinforced later in the 1980s when I was reviewing Interactive Video training programmes for the UK National Interactive Video Centre). I saw some great ‘interactive’ and engaging learning activities in those big 12” disks – the content was used to support experiential learning. At the same time I had the pleasure of sitting on the national steering committee of the TTNS service in the UK – an innovative collaboration between British Telecom and (I hardly bear mention in the current UK ‘hacking scandal’ climate) Rupert Murdoch’s News International. TTNS supported technology-based learning for schools and Further/Higher education in the UK. Every schoolchild in the UK had an email box on the Telecom Gold service – a very innovative step at the time.

Why Look Back?

The point of looking back is that it helps understand the fact that various forms of technology-based learning have been around for a long time, and that some of the pedagogies that were used in early days were equal, or superior, to the predominantly ‘course vending machine’ approaches that emerged in the late 1990s on the back of generic course catalogues and with content-led eLearning generally. Some of these 1990s models, to a greater or lesser extent, are still with us.

I think it’s a good time now to both look back and look forward and to re-think our approach to eLearning generally.

Significant Hurdles

Allison Rossett recently made it clear that there are still significant eLearning hurdles to jump in an article titled “Engaging with the new eLearning” published by Adobe. Allison pointed out that an observation she made almost 10 years ago still hasn’t been addressed. This is what she wrote in 2002:

“The good news is plentiful. eLearning enables us to deliver both learning and information at will, dynamically and immediately. It allows us to tap the knowledge of experts and non-experts and catapult those messages beyond classroom walls and into the workplace. And …it lets us know, through the magic of technology, who is learning, referring, and contributing—and who isn’t.

…Then there’s the bad news. Many simply fail to embrace eLearning. Like the sophomore taking a course called “Introduction to Western Civilization” via distance learning falling behind on assignments or the customer service representative who looks at two of the six eLearning modules and completes only one, or the supervisor, who had the best intentions, but is too busy with work to be anybody’s e-coach”.

Allison goes on to point out that “Every industry study reveals marked increases in training and development delivered via eLearning, often with disappointing numbers characterising participation and persistence….participants in eLearning programs are less likely to follow through than in an instructor-led program”.

This should give us cause to pause and think - and re-think - about our approach to eLearning . Not so much about eLearning as an approach in general - there’s plenty of evidence that it can be an effective way to assist and speed development - but we need to think about HOW we are employing and deploying eLearning. There’s clearly room for improvement there.

This also raises another fundamental question for me.

The question is this:

Where do current ideas about eLearning fit into the ‘new world’ of work and in the new world of building workforce capability in the 21st century?

A great deal has changed since the term eLearning first entered the vocabulary in 1999 and since web-based courses and modules started appearing in volume in the early 2000s. We need to rethink eLearning in light of these changes and other changes that are only now starting to impact the world of work.

The Changes Needed

A major driver for us to re-think eLearning approaches is the move away from the 20th Century ‘push’ models of learning - with modules, courses, content and curricula being pushed at employees.

We’re seeing a move towards a 21st Century ‘pull’ model - where workers ‘pull’ the learning and performance resources they need when they need to improve their work performance. They may need a course, but are more likely just to need some ‘here-and-now’ support to solve a problem or overcome an obstacle and then move on.

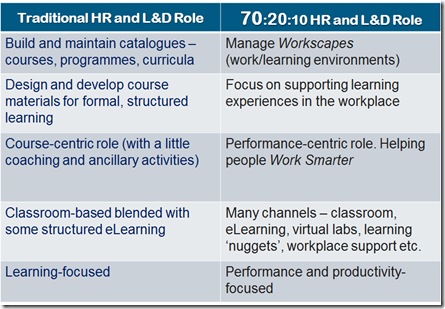

I see a requirement for two principal changes in thinking to address the challenge this change presents to Learning professionals. The changes are these:

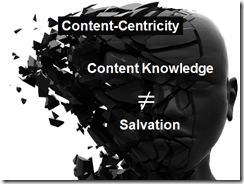

1. A move away from content-centric mind-sets.

2. A move away from ‘course’ mind-sets.

Step 1: Leaving Content-Centricity Behind

I’m sure most of us are aware that the major challenge for learning is no longer about ‘content’ or ‘knowledge’ (if it ever were).

I’m sure most of us are aware that the major challenge for learning is no longer about ‘content’ or ‘knowledge’ (if it ever were).

We can find content whenever we need it. Our lives are inundated with content. We may not have great filters for content – that’s the real challenge - but there is no doubt they will arrive in the next few years.

The need now is for other skills such as critical thinking and analysis skills, creative thinking and design skills, networking and collaboration skills, and, across all of these, effective ‘find’ skills.

The development of these new skills has nothing to do with content or ‘knowledge transfer’. It requires new mind-sets and capabilities that I’ve come to call ‘MindFind’ – mind-sets and capabilities that support us in finding the right content when we need it, at the point of need.

Obviously the need for content won’t go away completely, but we know that content is of greatest use when we can access it in the context of a specific challenge, not when we’re provided it in a class or an eLearning course and try to remember it until we take the end-of-course test - context is (almost) all.

We need an understanding of core concepts, certainly, but Learning professionals shouldn’t be wasting their time serving up all the details about ‘task’ in closed eLearning packages. They serves little purpose and the vast majority is forgotten immediately after the course or working through the eLearning modules.

The challenge for Learning professionals is all about helping workers make sense of what is expected of them, how they can gain the right experiences, how they can get opportunities to practice, how they can find the right people to help, and how they can have time to reflect on what they’ve done and what they’ve learned so they do it better next time. This is not achieved by creating and delivering learning ‘content’. It’s achieved by utilising the right context.

Content to Context

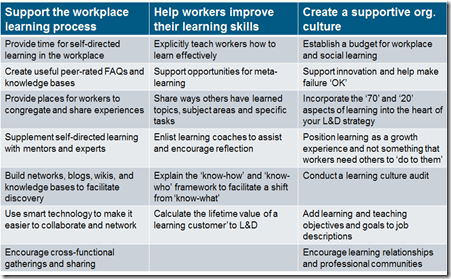

So we need to replace content with context – learning through doing, rather than learning through knowing.

We also need to move our focus from ‘know-what’ learning to ‘know-how’ learning. From content-rich to experience-rich. And from ‘know-what’ learning to ‘know-who’ learning as well – we are who we know, and our expertise is the sum of our own resources and others we can draw on when needed.

The latter is why social learning is such an important element in learning and needs more focus. It is not just ‘social’ for the sake of being social. Workers will want to co-create. Lots of the learning content of the future will be generated by people who are doing the work rather than by specialist training instructors and learning specialists. Learning professionals need to think about how they can facilitate and support this, rather than creating the next greatest content-heavy eLearning package. Instead they need to think about helping workers make connections and building communities where they can mine their own learning.

New Channels

Workers will also expect their learning to be more personalised and available in a self-service mode so they can get what they want when they want it and where they happen to be. That means Learning professionals need to consider new channels for learning.

Last month I was working at the Umm Al-Qura University in Mecca, Saudi Arabia with my Internet Time Alliance colleague Clark Quinn, and had the opportunity to ask the Dean of IT about the penetration of smartphones, notebooks and tablets among the 60,000 student population at the university. He estimated 90% had smartphones and at least 50% currently had tablets or notebooks. I am sure that penetration is even higher in many other parts of the world, and not just in the ‘developed’ world, either. A big part of the future of learning, as with our daily lives, is surely going to be mobile. We need to make sure that any content that really needs be made available to help with learning is accessible on multiple platforms.

More to the point, Learning professionals need to be thinking about creating learning EXPERIENCES rather than learning content.

As such, we need to move away from content-rich, experience-poor learning towards a focus on helping workers have rich learning experiences from which they can develop.

Step 2: De-Focusing from Courses

Many Learning professionals default to a course mind-set when faced with designing a solution to any performance problem. It’s an understandable response. That’s what most have done throughout their careers – design and deliver courses. Also, courses are relatively straightforward projects to undertake. Standard instructional design methodologies can be applied. They consist of a one-off event or a series of events that can be relatively easily scheduled and delivered. We know how long they’ll take, what resources they’ll use and we can manage the process quite easily.

Many Learning professionals default to a course mind-set when faced with designing a solution to any performance problem. It’s an understandable response. That’s what most have done throughout their careers – design and deliver courses. Also, courses are relatively straightforward projects to undertake. Standard instructional design methodologies can be applied. They consist of a one-off event or a series of events that can be relatively easily scheduled and delivered. We know how long they’ll take, what resources they’ll use and we can manage the process quite easily.

However, we also know that most learning doesn’t occur in courses or events. It occurs in the workplace, in bits-and-pieces. It occurs through watching an expert, or through a conversation we have with colleagues or a manager, or when we make a mistake and have the opportunity to reflect on how we’d do it next time, or in one of many other ways. Designing for learning in this environment is altogether different – and often a more ‘messy’ and complex matter. But outcomes are likely to be better. People are more likely to retain the learning they achieve through experience. And this type of ‘informal’ or workplace learning has been shown to be generally better received, more effective and less costly than its formal counterpart.

So de-focusing on courses and re-focusing on supporting learning in the workplace through social learning approaches and performance support will be critical in the future. There is no doubt about that.

In fact, there is a good basis of fact to argue that the real power of eLearning is social and contextual.

Those Learning professionals that understand and respond to this fact will be able to demonstrate greater impact. Those that stick to the content-rich, experience-poor models of the 20th Century will surely be overtaken by events.