The first chapter of ‘70:20:10 towards 100% performance’ (the recent book by Arets, Jennings & Heijnen) is titled ‘the training bubble’. It takes a quick look at the history, the lure, and some of the problems that have been brought about by thinking only in the formal training paradigm rather than in the performance paradigm.

The first chapter of ‘70:20:10 towards 100% performance’ (the recent book by Arets, Jennings & Heijnen) is titled ‘the training bubble’. It takes a quick look at the history, the lure, and some of the problems that have been brought about by thinking only in the formal training paradigm rather than in the performance paradigm.

The training bubble chapter starts by discussing our reliance on formal driver education and successful completion of a driving test as measures to ensure drivers are equipped to safely navigate our various nations’ roads.

Most countries have driver education and driving tests and, without exception, the assumption is that by requiring new drivers to undertake a formal education programme and the written and practical tests the probability of them having accidents will be lowered.

Formal Driver Education Does Not Reduce Accidents

However evidence suggests that formal driver education does not significantly reduce the risk of accidents when compared to learning in other ways, such as under the supervision and guidance of a usually older non-professional driver.

Willem Vlakveld, a psychologist and senior researcher at the Institute of Road Safety Research in the Netherlands has shown that not only does formal driver education not reduce accidents, but that intensive driver education (where new drivers undertake day-long consecutive driving lessons) is likely to lead to an even higher level of accidents in the first two years of driving when compared to more traditional, spaced, lessons.

In another research paper, Vlakveld reported that driving simulators may speed up skills acquisition, but will not help make novice drivers safer. In other words, simulations of real situations might help, but not necessarily in the way we might expect.

The Existing Driver Education Market is Going Nowhere, Fast

Despite the research, the formal driver education market is vast, and still growing. I read an article in the 19-20 March 2016 edition of China Daily while in that country. The China Daily article reported (on the basis of data obtained from the Ministry for Public Scrutiny) that China now has more than 300 million drivers, the highest in the world. It also estimated that this number will increase by 20 million each year in the foreseeable future.

Despite the research, the formal driver education market is vast, and still growing. I read an article in the 19-20 March 2016 edition of China Daily while in that country. The China Daily article reported (on the basis of data obtained from the Ministry for Public Scrutiny) that China now has more than 300 million drivers, the highest in the world. It also estimated that this number will increase by 20 million each year in the foreseeable future.

The article went on to report that this will create a training market worth more than 100 billion yuan (US$15.45 billion). Already technology is being used to help ramp-up the formal driver training industry boom (the photo on the right is illustrative of this).

The question this raises is ‘why would we encourage the development of a training industry using methods that have been shown to be ineffective in the past?’

Haven’t we, as professionals in the field of human learning and performance, learned anything ourselves?

I feel there is a fundamental lesson here for Learning and Development approaches generally.

Learning to drive a car is similar to many other skills acquisition processes. We develop capability through experience, practice, and reflection (individual and shared) over time. Often this capability-building is carried out with others. At other times it is done alone. Sometimes we may be able to increase the speed of acquisition of skills, but simply making formal education experiences more compressed or concatenated or more ‘sexy’ with technology won’t necessarily improve outcomes. Formal education and testing isn’t the key to improving performance. It’s the ‘70’ and ‘20’ learning – learning in context with plenty of practice – that that has most impact.

There are two elements that must be present when we need to improve our performance at achieving almost anything. First we must have the need and the desire to learn. And then we must spend plenty of time immersed in the environment where we are going to use our new skills and capabilities. Learning has its greatest impact the closer to the point of use it happens.

For driving motor cars, the first element is rapidly disappearing as technology overtakes the 20th century motor car, and the second – formal driver education - has been proven to be often ineffectual at helping reach the desired goal (driving safely).

The Very Short Lifespan of the Driving Test

A very short history of the driving test can teach us some lessons about the way we need to change and adapt to new conditions and to the evidence from research.

The driving test provides a ‘rite of passage’. Once a new driver completes the formal education and passes the test, the road is theirs. This is similar to almost any other formal education/test process, whether it’s an Microsoft MCSE or a Cisco CCNA technical ‘badge’ or a DMS or MBA business ‘badge’.

Yet in many ways the driving licence as we know it – a ‘badge’ received for scoring a ‘pass’ in the driving test - is fast becoming an artefact from a bygone era, even though it seems to have been with us forever.

In fact, the driving test in most countries is only a relatively recent development.

Karl Benz, the inventor of the modern automobile, needed written permission to operate his car on public roads in 1888. This was a licence of sorts, but there was no test.

Karl Benz, the inventor of the modern automobile, needed written permission to operate his car on public roads in 1888. This was a licence of sorts, but there was no test.

Compulsory driving testing was only formally introduced in the United Kingdom in 1934 (the first country to do so).

My father’s driving licence of July 1937 (here on the left) wouldn’t have required a test and I know my mother was never required to take a driving test throughout her life.

Some countries, such as Belgium, allowed people to drive without a test until relatively recently. In Belgium the driving test was only introduced in 1977. The Egyptian driving test until recently required the new driver to move just 6 metres forwards and backwards. The test is now more slightly challenging- drivers need to answer 10 questions (and get 8 correct) and negotiate a short S-shaped track.

As the driving test was gradually introduced across the world it was believed that formal driver education and the driving test reduced automobile-related deaths. That was the prime rationale.

We now know that’s not necessarily the case. Vlakveld and others burst that bubble some time ago. Yet we still persist.

In other words this formal training and test model is built on sand. Even though the authorities want to believe it has a positive impact, the research suggests it doesn’t.

Of course this is no reason to dismiss all formal training and testing out-of-hand. However, it should make us question our assumptions that formal training and testing (whether classroom-based or through eLearning) will change behaviour and build high performance. To build or even maintain our performance we need to continuously use our new-found skills. That’s obvious. It also helps if we are continually aware of the changes occurring around us and we have the ability to adapt to changing conditions.

In other words, we need continuous practice to build and maintain performance in any domain. And that practice needs to be ‘match practice’.

Match Fitness

‘Match fitness’ is a well-known phenomenon.

‘Match fitness’ is a well-known phenomenon.

No matter how good your training (or your driver education) you need time to use your skills and capabilities in the flow of work (or on the playing field) before you can perform even adequately, let alone exceptionally. Performance is highly context sensitive. How many of us have shown we can deliver a great tennis serve or hit a long golf shot on the practice court or course, or deliver a compelling speech, only to make a hash of things once we step into a competitive game or onto a stage in front of hundreds of people?

And how many of us, on first passing our driving test , were disappointed that a parent refused to let us borrow their car because they thought we needed ‘more time to practice’. We’d passed the test, for goodness sake!!

Ted Gannan, the CEO of a performance support company in Australia has explained the need to regularly apply skills in the workplace in this short ‘match fitness’ article. It’s worth a read.

The Distance Between Passing the Test and High Performance

The distance between formal driver education, passing the test, and high performance behind the wheel is often a huge one. And mastery doesn’t come without time and experience in context. In our daily work we also need ‘match fitness’ in order to perform at our best. We tend to forget that fact. Tests and simulations aren’t suitable proxies. Formal training may sometimes be needed, but it’s never enough.

The End of the Driver Education Industry

There is another factor that’s driving the demise of the formal driver education industry. This could also serve as a lesson for us in other formal training endeavours.

There is another factor that’s driving the demise of the formal driver education industry. This could also serve as a lesson for us in other formal training endeavours.

It’s likely that the current generation of prospective drivers enrolling on their driving courses will be the last.

Motor cars are becoming more like computers. The human-motor car interface is changing. Hands-free,voice-enabled interaction is becoming commonplace. Transport, like many other aspects of our life, is being re-imagined. The skills we needed in the past are no longer needed, or being replaced with the need for new sets of skills.

According to KPMG auto industry experts, the driverless car is analogous to the smartphone. KPMG predicts huge growth in autonomous cars and an increase not just in general usage but also in the nature of use. ‘Uber without a driver’ services and other innovations are getting ready to come on-stream. Some of it is already happening.

In a few short years we’ve come from some basic performance support in our cars – cruise control, electronic stability, park assist (1990s); through to the Tesla Autopilot, GM Super Cruise, and the Google Car (2010s); and we know that full self-Driving Automation is not far off.

Is the formal driver education industry adapting and preparing for these dramatic changes?

Is the formal driver education industry adapting and preparing for these dramatic changes?

The answer to this is question is ‘not much, if at all’.

Learner drivers still receive similar types of instruction to that delivered 50 years ago. The industry has changed very little apart from the increased use of technology in the form of simulators.

All this sounds like many other areas of formal education and training. Methods have not changed much. Some technology may have been introduced to make the process ‘more interesting’ or to allow scaling, but overall the out-of-context way we design and deliver most training is still the dominant approach.

All this despite the fact we know that continuous learning in the context of the workflow is almost always the best way to develop proficiency and build high performance. We know that formal education in many areas of enterprise does not have the impact we desire or expect. It’s not just in driver education. It’s in almost every sphere of activity. We need to think and act in new ways if we’re not to follow formal driver education down the carbon monoxide mine-shaft.

There is an answer to this conundrum. We need to bring learning and working together, not use one as a proxy for the other.

To learn more about developing approaches that exploit the ‘70’ and ‘20’ – learning as part of working – read the book ‘70:20:10 towards 100% performance’ or visit the 70:20:10 Institute website.

References:

70:20:10 towards 100% performance (2015). Arets, Jennings & Heijnen. Sutler Media

Hazard Anticipation of Young Novice Drivers (2011). Willem Pieter Vlakveld https://www.swov.nl/rapport/Proefschriften/Willem_Vlakveld.pdf

2016 Internet Trends (2016). Mary Meeker. http://www.slideshare.net/kleinerperkins/2016-internet-trends-report

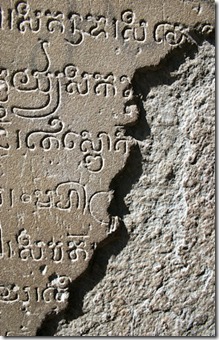

Classroom education emerged in a world of information paucity. A minority of people could read. Knowledge was held by the few and education was deeply entwined in the oral tradition. Many of the early education models in the West were driven by religious texts that were read aloud. Memorization was a critical skill. Rote learning was the way to get ahead. The classroom was a critical tool.

Classroom education emerged in a world of information paucity. A minority of people could read. Knowledge was held by the few and education was deeply entwined in the oral tradition. Many of the early education models in the West were driven by religious texts that were read aloud. Memorization was a critical skill. Rote learning was the way to get ahead. The classroom was a critical tool.

The Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies’ 10th Anniversary ‘Top Tools for Learning’ Survey closes midday UK time on Friday 23 September 2016.

The Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies’ 10th Anniversary ‘Top Tools for Learning’ Survey closes midday UK time on Friday 23 September 2016. If you haven’t already voted in this survey, please take a visit

If you haven’t already voted in this survey, please take a visit

![[extending%2520learning%255B4%255D.png]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-_i9nGfZQK0w/VUlUfBoipDI/AAAAAAAABM8/P3a8cVFPquQ/s1600/extending%252520learning%25255B4%25255D.png)